The Vietnam War lasted from 1955 to 1975 and occurred in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. The United States supported South Vietnam against North Vietnam and the Viet Cong, who were supported by a number of communist countries. After two decades of fighting, the North Vietnamese won the war, and North and South Vietnam were reunited with North Vietnam to create a the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

Journalism shifted significantly during the Vietnam War. Journalists had previously covered wars by using press conferences and briefings by the United States government; this time, they sent journalists to cover the war on the ground and use their own research and reporting. During the war, a whistleblower named Daniel Ellsberg leaked the Pentagon Papers to Washington Post reporter Ben Bagdikian. Those documents uncovered government lies and started to shift the public’s perception of the war after Bagdikian gave them to a senator to be read into the public record. Once the media started showing how badly the war was going, many Americans stopped supporting the war.

Videos

On Nov. 12, 1969, reporter Seymour Hersh broke a shocking story about a massacre of hundreds of unarmed men, woman and children in the South Vietnamese hamlet of My Lai. Hersh explains that the story started with an anonymous tip and led him to Fort Benning, Georgia, where the Army…

Tags

Share

The following URL links directly to the video or page.

Copy and paste the code into your website to embed this video.

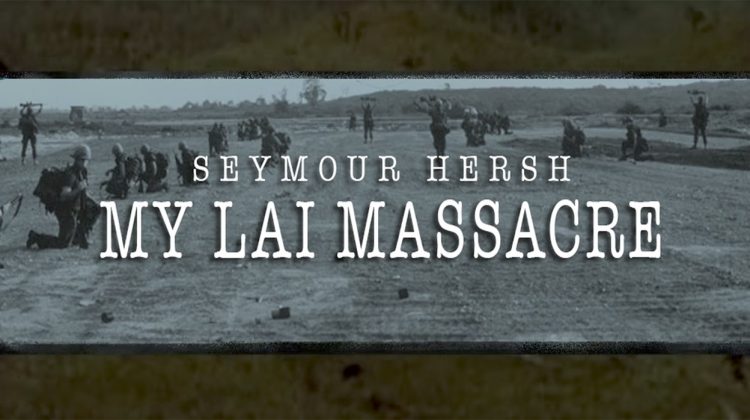

Ben Bagdikian remembers how he obtained a copy of the Pentagon Papers, a secret Defense Department history of U.S. involvement in Vietnam, leaked by Daniel Ellsberg.

Tags

Share

The following URL links directly to the video or page.

Copy and paste the code into your website to embed this video.

Bill Kovach remembers helping The New York Times reporter Neil Sheehan get the Pentagon Papers out of Boston and down to New York.

Tags

Share

The following URL links directly to the video or page.

Copy and paste the code into your website to embed this video.

Daniel Schorr was investigated by J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI and placed on President Richard Nixon’s enemies list.

Tags

Share

The following URL links directly to the video or page.

Copy and paste the code into your website to embed this video.

Historical Timeline

Click on individual events to expand items one by one, or click the expand all button to view the entire contents of the timeline.

1954

- Dien Bien Phu

-

May 7, 1954

The eight-year French-Indochinese War concludes with an overwhelming French defeat at the battle of Dien Bien Phu. The ensuing peace conference in Geneva divides Vietnam (formerly Indochina) into a communist-controlled North and an allegedly democratic South.

1961

- JFK Inauguration Promise

-

January 20, 1961

At his inauguration, President John F. Kennedy promises aggressive support for America’s friends and vehement resistance to its foes.1 Stressing the need for containment of communism in Southeast Asia and citing the domino theory that if one nation falls to communism, neighboring states will follow, Kennedy and his successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, slowly escalate U.S. military presence in Vietnam.

1964

- Tonkin Incident

-

August 5, 1964

President Johnson addresses the nation, declaring that while on “routine patrol” in the Gulf of Tonkin, U.S. warships had been deliberately attacked by North Vietnamese torpedo boats. It emerges years later that this attack never actually happened.

- LBJ to Congress

-

August 6, 1964

President Johnson goes to Congress to ask for permission to use military force in Southeast Asia, without seeking a formal declaration of war.2 The press almost universally applauds his actions, The Washington Post declaring, “President Johnson has earned the gratitude of the free world as well as the nation for his careful and effective handling of the Viet-Nam crisis.”3

- Tonkin Resolution

-

August 7, 1964

Congress passes the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution authorizing the use of conventional military force in Southeast Asia.

- Stone’s Skepticism

-

August 24, 1964

I.F. Stone, one of the few journalists to voice skepticism about the resolution and the Gulf of Tonkin incident that prompted it, writes one of the first investigative reports on the attack, raising questions about lack of proof.4 The report begins, “The American government and the American press have kept the full truth about the Tonkin Bay incidents from the American public.”5

1965

- Rolling Thunder

-

March 2, 1965

Operation Rolling Thunder begins. It is one of the most intense, yet least successful, aerial bombardment campaigns in military history. The operation intends to discourage the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) from any incursion in South Vietnam while simultaneously avoiding the engagement of U.S. ground troops. Operation Rolling Thunder ends four years later after dropping 864,000 tons6 of American bombs on North Vietnam.

- Ground Forces Arrive

-

March 8, 1965

The first U.S. ground forces arrive in South Vietnam. Initially, 3,500 Marines are deployed only to defend Air Force bases, but by the end of the year, troop levels swell to more than 200,000.7 By 1968, there are 537,377 U.S. troops in Vietnam.8

1966

- LBJ Makes Case

-

January 12, 1966

President Johnson makes his case for staying in Vietnam in his State of the Union address. “We do not intend to abandon Asia to conquest,” he states. “The enemy is no longer close to victory. Time is no longer on his side. There is no cause to doubt the American commitment.”9

- RFK Criticizes

-

January 31, 1966

Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, D-N.Y., criticizes President Johnson’s policy and the resumption of bombing in Vietnam, stating that the bombing “may become the first in a series of steps on a road from which there is no turning back — a road that leads to catastrophe for all mankind.”10

- Aid is Stolen

-

November 12, 1966

The New York Times reports that much of the economic aid sent to Saigon is stolen or ends up on the black market.11

1967

- ‘Arrogance of Power’

-

January 23, 1967

Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman J. William Fulbright, D-Ark., publishes “The Arrogance of Power” criticizing U.S. policy in Vietnam and the stated justifications for the war. The book is based on a statement made before the Foreign Relations Committee in which he declared, “Some of our super-patriots assume that any war the United States fights is a just war, if not indeed, a holy crusade, but history does not sustain their view. … I fail to understand what is reprehensible about trying to make moral distinctions between one war and another — between, for example, resistance to Hitler and intervention in Vietnam.”12

- McNamara Admission

-

August 9, 1967

Closed-door hearings of the Senate Armed Services Committee begin. Defense Secretary Robert McNamara tells the committee that U.S. bombing would not be enough to stop the flow of supplies from North Vietnam to South Vietnam. The flow, he says, “cannot be stopped by air bombardment — short of virtual annihilation of North Vietnam and its people.”13

1968

- Tet Offensive

-

January 31, 1968

North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces launch the Tet Offensive, a massive attack that reaches far into South Vietnam. While the U.S. and South Vietnamese militaries are initially surprised at such a coordinated assault, they secure a tactical victory. Most Americans at home, however, are shocked that a supposedly weakened enemy could conduct such a synchronized attack.

- Tonkin Hearings

-

February 20, 1968

The Senate Foreign Relations Committee begins a hearing on what actually happened during the Gulf of Tonkin incident four years earlier. During closed-door testimony not released to the public until more than 30 years later, senators express their regret and anger over authorizing the president to wage war in Vietnam under false pretenses. Even Missouri Democratic Sen. Stuart Symington, a prominent hawk, decries “this stupid war.”14

- Cronkite Report

-

February 27, 1968

After traveling to Vietnam to report on the Tet Offensive, respected CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite calls the Vietnam conflict “a stalemate” and advises a “negotiated peace.”15

- LBJ Drops Out

-

March 31, 1968

The initial effectiveness of the Tet Offensive combined with increasingly critical news coverage contribute heavily to President Johnson’s decision not to seek reelection.

- Times Editorial

-

August 11, 1968

Press criticism of the war intensifies. A New York Times editorial states: “A bad war simply cannot produce a victorious peace. This is the truth that the nation confronts over Vietnam.”16

1969

- Cambodia Bombing Begins

-

March 17, 1969

Based on intelligence about the location of the secret North Vietnamese headquarters, the White House authorizes bombing of Cambodia. This expansion of the war into a neutral country is kept secret from the press and the public. “Should the press persist in its inquiries … U.S. spokesman will neither confirm nor deny reports of attacks on Cambodia,” a top military official writes in a cable sent shortly before the bombing begins.17

- Cambodia Bombing leaked

-

May 9, 1969

William Beecher, military correspondent for The New York Times, breaks the news of the Nixon administration’s secret bombings of Cambodia.18 The bombings were planned as retaliation for PAVN/NLF forces’ launch of rocket and artillery attacks against South Vietnam. The bombing mission was not authorized by Congress and had been kept secret from even the secretary and chief of staff of the Air Force.19 In trying to find how information on the bombings had been leaked, the White House authorizes FBI wiretaps on Beecher’s phone along with those of officials on the National Security Council and in the Pentagon.20 One of those whose telephones is tapped is Morton Halperin, a National Security Council staffer who the White House believes — erroneously — is the source of the Cambodia leak. After Nixon’s resignation, Halperin sues the disgraced president and his aides in federal court on the grounds that the wiretap on his home telephone violated his Fourth Amendment rights. A judge rules in his favor, and he is awarded a symbolic $1 in damages.21

- D.C. Demonstration

-

October 15, 1969

Hundreds of thousands of people converge on Washington for a demonstration calling for the end of the war. The event, dubbed the Peace Moratorium, is one of the largest political demonstrations ever held in Washington.22

- My Lai Massacre

-

November 13, 1969

In the first of a three-part, Pulitzer Prize-winning series, investigative reporter Seymour M. Hersh breaks a story about American soldiers’ merciless murders of hundreds of Vietnamese civilians at My Lai. News of the March 16, 1968, massacre horrifies U.S. citizens as many question the behavior of U.S. soldiers in Vietnam as well as the overall purpose of the war. Hersh quotes Sgt. Maj. Michael Bernhardt: “The whole thing was so deliberate. It was point-blank murder and I was standing there watching it.”23 The massacre itself had occurred more than a year earlier, and after Hersh uncovered the truth, he says 30 major news organizations rejected his story. “Look [magazine] turned me down … and an editor at Life said it was out of the question,” Hersh states.24

1970

- Nixon Acknowledges Cambodia Bombing

-

April 30, 1970

President Nixon finally announces the decision to attack NVA positions in Cambodia. He promises the campaign in Cambodia will be over by June 30.

- Kent State Shootings

-

May 4, 1970

As domestic opposition to the Vietnam War escalates, widespread demonstrations are organized to protest the U.S. invasion of Cambodia. At Kent State University, the Ohio National Guard shoots into throngs of unarmed student protesters, killing four and wounding nine.25 The Kent State shootings become a microcosm of the social and political divisions present during the Vietnam War.26

1971

- Fulbright Hearings

-

April 22, 1971

John Kerry, representing Vietnam Veterans Against the War and testifying before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, calls for the immediate and unilateral withdrawal of U.S. troops from Vietnam.27 These hearings, chaired by Sen. Fulbright, are instrumental in altering American opinion of the conflict.

- Pentagon Papers

-

June 13, 1971

Daniel Ellsberg, a former Pentagon aide and a RAND Corporation analyst, leaks a top-secret Department of Defense report on the history of U.S. political and military involvement in Vietnam from 1945 to 1967 to Neil Sheehan of The New York Times. The newspaper publishes excerpts from the report, soon known as the Pentagon Papers. The first article begins, “A massive study of how the United States went to war in Indochina, conducted by the Pentagon three years ago, demonstrates that four administrations progressively developed a sense of commitment to a non-Communist Vietnam, a readiness to fight the North to protect the South, and an ultimate frustration with this effort — to a much greater extent than their public statements acknowledged at the time.”28 The report exposes the secret history of the conflict and widens the credibility gap between the Nixon administration and the American people. Incensed and embarrassed, the government attempts to prevent the publication of additional stories based on the Pentagon Papers by, for the first time in U.S. history, trying to use the court system to stop a newspaper from printing. The government succeeds in getting a temporary federal injunction against the Times.

- Post Publishes Papers

-

June 18, 1971

Ellsberg takes the report to The Washington Post. Though extremely worried about retaliation from the administration, the Post begins publishing the Pentagon Papers. The next day, Attorney General William Rehnquist calls the newspaper, demanding it halt any further publication. Executive Editor Ben Bradlee replies, as had The New York Times, that he “must respectfully decline.”29 Again, the government seeks an injunction from the courts, citing the Espionage Act of 1917. This time the attempts are unsuccessful. Though the courts agree that, in cases of clear national security, a newspaper can be prevented from printing, they rule that the administration had not met the burden of proof for that to occur. In New York, further arguments are heard and the temporary restraining order against the Times is lifted. Judge Murray Gurfein: “The security of the nation is not at the ramparts alone. Security also lies in the value of our free institutions. A cantankerous press, an obstinate press, an ubiquitous press must be suffered by those in authority in order to preserve the even greater values of freedom of expression and the right of the people to know.”30 The report continues to be published, and on June 28, in a 6-3 decision, the Supreme Court upholds the newspapers’ right to publish.31

1973

- Paris Peace Accords

-

January 27, 1973

The U.S. and North Vietnam sign the Paris Peace Accords, laying out a formal plan for the end of U.S. military engagement in Vietnam. It took more than five years of on-and-off negotiations, both in public and in secret, to reach an agreement that both countries found acceptable. The agreement allows Nixon to argue that he delivered on his campaign promise of “peace with honor.”32

1975

- U.S. Leaves Vietnam

-

April 30, 1975

After 11 years and more than 58,00033 American lives lost (along with the lives of 63 journalists — a number surpassed only by the recent Iraq War34), the last U.S. helicopter leaves Saigon as North Vietnamese forces overrun the South Vietnamese capital. The NVA’s guerrilla tactics and incredible resolve, combined with U.S. domestic opposition, pivotal events such as the Kent State shootings, the Fulbright hearings and the publishing of the Pentagon Papers, bring an end to the American presence in Vietnam.

Recommended References

ONLINE RESOURCES

- 1971: Year in Review

- Complete text of the Pentagon Papers

- The Texas Tech University Vietnam Virtual Archive

- PBS American Experience: Vietnam Online

DOCUMENTARIES

- Remember My Lai. Prod. Kevin Sim and Michael Bilton. PBS “Frontline,” 1989.*

- Regret to Inform. Filmmaker Barbara Sonneborn. PBS, P.O.V./American Documentary Inc., 2006.**

*DuPont-Columbia Golden Baton Award winner

**Peabody Award winner

BOOKS

- Ahern, Thomas L., Jr. Vietnam Declassified: The CIA and Counterinsurgency. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2010.

- Ellsberg, Daniel. Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers. New York: Penguin Putnam, 2002.

- Emerson, Gloria. Winners & Losers: Battles, Retreats, Gains, Losses and Ruins From a Long War. New York: Random House, 1976.

- Fitzgerald, Frances. Fire in the Lake: The Vietnamese and the Americans in Vietnam. New York: Vintage Books, 1972.*

- Fullbright, J. William. The Arrogance of Power. New York: Random House, 1967.

- Galloway, John. The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. Rutherford, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1970.

- Griffiths, Philip Jones. Agent Orange: “Collateral Damage” in Vietnam. London: Trolley Ltd., 2003.

- Halberstam, David. The Best and the Brightest. New York: Ballantine Books, 1969.

- Halberstam, David. The Making of a Quagmire: America and Vietnam During the Kennedy Era. New York: Roman & Littlefield Publishers, 2008.

- Hammond, William M. Reporting Vietnam. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1998.

- Hendrickson, Paul. The Living and the Dead: Robert McNamara and Five Lives of a Lost War. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1996.

- Hersh, Seymour M. The Price of Power: Kissinger in the Nixon White House. New York: Summit Books, 1983.

- Hersh, Seymour M. My Lai 4: A Report on the Massacre and Its Aftermath. New York: Random House, 1970.

- Herr, Michael. Dispatches. New York: Avon Books,1968.

- Kaiser, David. American Tragedy: Kennedy, Johnson, and the Origins of the Vietnam War. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000.

- Karnow, Stanley. Vietnam: A History. New York: Viking Press, 1983.

- Langguth, A.J. Our Vietnam: The War 1954-1975. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000.

- Laurence, John. The Cat From Hue: A Vietnam War Story. New York: PublicAffairs, 2002.

- Maclear, Michael. The Ten Thousand Day War: Vietnam 1945-1975. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1981.

- MacPherson, Myra. Long Time Passing: Vietnam and the Haunted Generation. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1984.

- Maraniss, David. They Marched into Sunlight: War and Peace, Vietnam and America, October 1967. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2003.

- McMaster, H.R. Dereliction of Duty: Lyndon Johnson, Robert McNamara, the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Lies That Led to Vietnam. New York: HarperCollins, 1997.

- McNamara, Robert S. In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam. New York: Times Books, 1995.

- Moise, Edwin E. Tonkin Gulf and the Escalation of the Vietnam War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

- The Pentagon Papers: As Published by The New York Times. New York: Quadrangle Books, 1971.

- Prados, John and Margaret Pratt Porter, eds. Inside the Pentagon Papers. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2004.

- Prochnau, William. Once Upon a Distant War: Young War Correspondents and the Early Vietnam Battles. New York: Random House, 1995.

- Reporting Vietnam: American Journalism 1959-1975. New York: Literary Classics of the United States, 1998.

- Schulzinger, Robert D. A Time for War: The United States and Vietnam, 1941-1975. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Shapley, Deborah. Promise and Power: The Life and Times of Robert McNamara. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1993.

- Shawcross, William. Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon and the Destruction of Cambodia. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1987.

- Sheehan, Neil. A Bright Shining Lie: John Paul Vann and America in Vietnam. New York: Vintage Books, 1988.*

- Sheehan, Neil. The Arnheiter Affair. New York: Random House, 1971.

- Ungar, Sanford J. The Papers & The Papers: An Account of the Legal and Political Battle Over the Pentagon Papers. New York: Columbia University Press, 1989.

- Wells, Tom. The War Within: America’s Battle Over Vietnam. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.

- Windchy, Eugene G. Tonkin Gulf. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1971.

- Wyatt, Clarence R. Paper Soldiers: The American Press and the Vietnam War. New York: W.W. Norton, 1993.

* Pulitzer Prize winner

ENDNOTES

- 1 Langguth, A.J. Our Vietnam: The War 1954-1975. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000: 112.

- 2 “Stern Crisis” editorial. Washington Post 6 Aug. 1964.

- 3 The Best of I.F. Stone. New York: PublicAffairs: 247-255.

- 4 Stone, I.F. “What Few Knew About the Tonkin Bay Incidents.” I.F. Stone’s Weekly (Special Issue on Indochinese War) 24 Aug. 1964.

- 5 Cummins, Joseph. Why Some Wars Never End: The Stories of the Longest Conflicts in History. Beverly, MA: Winds Press, 2010: 184.

- 6 Kane, Tim, and David D. Gentilli. “Is Iraq Another Vietnam? Not for U.S. Troop Levels.” The Heritage Foundation, September 2004.

- 7 Johnson, Lyndon Baines. “State of the Union Address.” 12 Jan. 1966.

- 8 Peters, Charles. Lyndon B. Johnson. New York: Times Books, 2010.

- 9 “Vast U.S. Aid Loss in Vietnam Denied,” New York Times 18 Nov. 1966.

- 10 Fulbright, J. William. The Arrogance of Power. New York: Random House, 1967.

- 11 McNamara, Robert S. et al. Argument Without End: In Search of Answers to the Vietnam Tragedy. New York: PublicAffairs, 1999: 252.

- 12 “Senate Foreign Relations Committee Releases Volumes of Previously Classified Transcripts from Vietnam Era Hearings.” Press release, Senate Committee on Foreign Relations 14 Jul 2010.

- 13 Martin, Douglas. “Walter Cronkite, 92, Dies; Trusted Voice of TV News.” New York Times 17 July 2009.

- 14 “For Vietnam Peace.” Editorial. New York Times 11 Aug. 1968.

- 15 Shawcross, William. Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon and the Destruction of Cambodia. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1987: 19-22.

- 16 Beecher, William. “Cambodia Raids Go Unprotested,” New York Times 9 May 1969.

- 17 Wyatt, Clarence R. Paper Soldiers: The American Press and the Vietnam War. New York: W.W. Norton, 1993: 208.

- 18 “Aides Confirm Nixon Okayed Pentagon Taps.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette 16 May 1973.

- 19 Morton Halperin et al., v. Henry Kissinger et al. 606 F.2d 1192. D.C. Circuit Court. 1979.

- 20 “On This Day, 1969: Millions March in Vietnam Moratorium." BBC 15 Oct. 1969.

- 21 Hersh, Seymour M. “Hamlet Attack Called ‘Point-Blank Murder.’” St. Louis Post-Dispatch 20 Nov. 1969.

- 22 Wyatt, 207-208.

- 23 Kifner, John. “4 Kent State Students Killed by Troops.” New York Times 5 May 1970.

- 24 Lewis, Jerry M., and Thomas R. Hensley. “The May 4 Shootings at Kent State University: The Search for Historical Accuracy.” Ohio Council for the Social Studies Review 34(1) 1998: 9-21.

- 25 “Complete testimony of Lt. John Kerry to Senate Foreign Relations Committee.” Congressional Record 22 Apr. 1971.

- 26 Sheehan, Neil. “Vietnam Archive: Pentagon Study Traces 3 Decades of Growing U.S. Involvement.” New York Times 13 June 1971.

- 27 Sachs, Stephen E. “‘All the News That’s Fit to Print’: The New York Times and the Pentagon Papers”1996.

- 28 Finan, Christopher M. From the Palmer Raids to the Patriot Act: A History of the Fight for Free Speech in America. Boston: Beacon Press, 2007: 231.

- 29 Stone, Geoffrey R., Perilous Times: Free Speech in Wartime: From the Sedition Act of 1798 to the War on Terrorism. New York: W.W. Norton, 2004.

- 30 “People and Events: Paris Peace Talks.” PBS “American Experience.”

- 31 Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund.

- 32 Santora, Mark, and Bill Carter. “For Journalists, Iraq Becomes Deadliest War.” New York Times 30 May 2006.

My Lai Massacre

My Lai Massacre  My Lai Massacre

My Lai Massacre  Obtaining the Pentagon Papers

Obtaining the Pentagon Papers  Obtaining the Pentagon Papers

Obtaining the Pentagon Papers  Daniel Ellsberg and The Pentagon Papers

Daniel Ellsberg and The Pentagon Papers  Daniel Ellsberg and The Pentagon Papers

Daniel Ellsberg and The Pentagon Papers