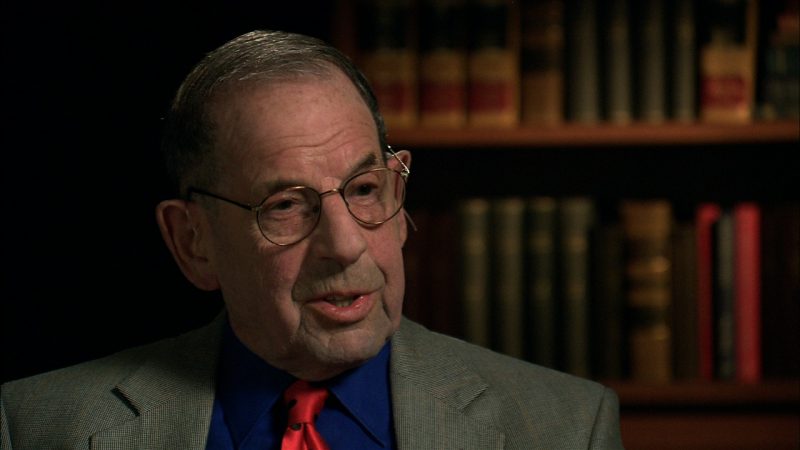

A Washington Post reporter for 39 years, Murrey Marder covered the Alger Hiss trial as well as Joseph McCarthy. His reporting led to the1954 Army-McCarthy hearings that marked the beginning of the end of the Wisconsin senator. Marder also covered the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin Resolution and founded and funded, from his life savings, the Nieman Watchdog Project at Harvard University. He died March 11, 2013, at the age of 93.

Affiliations (past and present)

Topics

Videos

The late Murray Marder was a reporter for The Washington Post, who covered Sen. Joseph McCarthy, R-Wis., for more than five years. He talks about what it was like covering McCarthy day in and day out.

Share

The following URL links directly to the video or page.

Copy and paste the code into your website to embed this video.

Career Timeline

1936

Marder starts his journalism career when he was 17 years old by landing a job as a copy boy at the Philadelphia Evening Ledger.

1940

Working under apprenticeship as a copy boy for four years, Marder learns the ropes of journalism and becomes a reporter at 21.

1941

As the United States enters World War II , Marder joins the combat correspondent program in the Marine Corps. The assignment sends Marder to the South Pacific, where he is in four combat operations.

1945

By the end of the war, Marder is in charge of the Marine Corps news desk in Washington.

1946

Marder joins The Washington Post, where he would work for 39 years.

1949

On his first big story, Marder is sent to cover the Alger Hiss case . A former State Department official who later became president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Hiss was indicted on charges that he had passed secret government documents to the Soviet Union in the 1930s while working at the Department of State. The case is still disputed today .

1950

Marder is awarded a Nieman Fellowship at Harvard University.

1953

Taking over the “Red Beat” from Al Friendly, Marder is assigned full time to cover Sen. Joseph McCarthy. The Wisconsin senator had conducted hundreds of investigations and trials , accusing people of being communists or supporting communism. Marder’s role as a reporter is unique in that it was not rote repeating of assertions but he tried to place McCarthy and his actions in the fullest possible context. In his book “The Powers That Be,” David Halberstam described Marder as “the perfect choice for the assignment, quiet, intelligent, dogged and meticulous. There was nothing flashy about a Marder story, no one ever accused him of deft or imaginative prose, but he was above all else careful and fair.” Marder, along with Baltimore Sun reporter Phil Potter, is one of the first journalists to challenge McCarthy for his baseless accusations.

Marder’s biggest story comes in the fall of 1953 after looking into McCarthy’s claims of rampant espionage at Fort Monmouth in New Jersey. Marder discovers that all 33 alleged cases of espionage were untrue. After extensive reporting, he writes several stories outlining the false accusations made by McCarthy. At a news conference with Robert Stevens, the secretary of the Army, Marder is relentless with his questioning, until Stevens admits that in fact there had been no evidence of spying in the Fort Monmouth cases.

1957

Marder opens the London bureau for The Washington Post, the first bureau of the Washington Post Foreign Service. As chief diplomatic correspondent for the newspaper, Marder travels worldwide with government officials.

1964

On Sunday night, Aug. 2, Marder happens to be in the press room at the State Department when The Associated Press reports that North Vietnamese patrol boats had attacked two U.S. destroyers. Marder later recalled, “I looked at this and I thought, well, that’s strange. I have been on torpedo boats. And torpedo boats are not equipped to attack destroyers.” He speaks to a trusted State Department intelligence source on the phone and asks him bluntly, “What were we doing to them to provoke them to do this?” Marder persuades him to admit that “Yes, we had been conducting some operations there.”

His source could not be quoted by name, and there is another problem by the time of President Lyndon Johnson’s first public statements to the nation about the attack. The Washington Post had already editorially endorsed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which soon became the de facto declaration of war by the U.S. Congress throughout the Vietnam War. Most major newspapers in America supported Johnson in editorials, and 85 percent of Americans polled supported the U.S. bombing raids. Just three months before the election, the president’s overall approval rating jumped 30 points, from 42 percent to 72.

1971

After The New York Times had been prevented from publishing the secret internal Defense Department history of the Vietnam War known as the Pentagon Papers, the Washington Post picks up where the Times had left off. In addition to having a byline on the first Pentagon Papers story in the Post, Marder takes part in the debate at Post executive editor Ben Bradlee’s house on whether the newspaper should publish the Pentagon Papers.

1978

Marder is awarded the Whitney H. Shepardson Fellowship from the Council on Foreign Relations.

1985

After nearly four decades of reporting, Marder retires from the Post.

1996

Donating a large portion of his individual financial resources to Harvard, Marder is instrumental in helping to conceive and launch the Nieman Foundation’s Watchdog Project .

2003

Marder criticizes the media’s role in the coverage of the invasion of Iraq in an article for Harvard publication Nieman Reports called “What Happens When Journalists Don’t Probe?”

2008

Continuing to provide commentary for the Nieman Watchdog blog, Marder focuses on transparency and accountability of the government and the critical role of the media in ensuring it.

2013

Marder's death inspires a tribute by Charles Lewis.

Additional Information and References

Sources

- Council on Foreign Relations

- Halberstam, David. “The Powers That Be.” New York: Knopf, 1979.

- Interview with Charles Lewis, April 26, 2007, Washington, D.C.

- Marder, Murrey. “What Happens When Journalists Don’t Probe?” Nieman Reports, Summer 2003.

- Nieman Watchdog Project